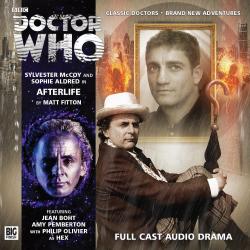

Afterlife (Big Finish)

Sunday, 6 April 2014 - Reviewed by

Strangely enough for an audio drama which packs countless nods to the past and exists entirely within the continuity of Doctor Who’s ‘classic’ era, Matt Fitton’s latest Seventh Doctor release captures the essence of modern-day Who more faithfully than any of its predecessors. Where the show in its 1980s guise would rarely place a significant focus on the consequences of the titular Madman with a Box’s journeys through time and space, barely an episode goes by these days without a past action coming back to haunt the character or a spur-of-the-moment decision forcing him to contemplate the limits of his moral compass and the extent of his ability to aid those in need of liberation. No longer will a regeneration be casually cast aside mere moments into the new Doctor’s first adventure, nor a companion’s departure left unacknowledged in the episodes which follow it. Afterlife gracefully echoes this grounded, sympathetic take on the Time Lord’s adventures and their effects on his assistants, and- despite a few tonal mishaps along the way- comes off all the better for it.

In stark contrast to recent Big Finish releases such as Dark Eyes 2, the premise of Fitton’s narrative is relatively straightforward: Thomas Hector Schofield (better known to Doctor Who fans as ‘Hex’) was killed by Fenric in 2012’s Gods and Monsters, a calamitous event which has (with good reason) turned Ace against the Doctor, leaving the latter to contemplate how to redeem himself after his being directly connected to the demise of one of his most loyal allies. Not since Earthshock and (albeit briefly) Time-Flight has a pre-21st Century Who yarn sought to have its eternal protagonist’s psyche and endless internalised guilt go quite so far under the microscope, and indeed, Fitton utilises the rarity of such a narrative opportunity as this to his significant advantage, providing a script which offers its lead stars their strongest material in years in terms of emotional and dramatic scope for future development. If there remain fans out in the big wide world who doubt Sylvester McCoy and Sophie Aldred’s talents, then this just might be the drama to convince them otherwise.

Inevitably, Ace is of the most paramount importance to the listener (and her ‘screen time’ reflects this suitably) as their entry point into proceedings, and to this degree, Aldred conveys beautifully the pathos of the character’s loss of a close friend, of someone who perhaps could have been something more than that had he not bitten the proverbial bullet before his time. Too often in the final episodes of the show’s 1980s run before its cancellation, this feisty and yet wholly sympathetic companion was cruelly robbed of a satisfying personal arc, with The Curse of Fenric coming the closest to matching Father’s Day and The Fires of Pompeii in its representation of its human protagonist’s utter disbelief at their extra-terrestrial hero’s detachment from emotion, yet still somehow falling short. In this respect, Afterlife excels without limits, casting Ace in an entirely new light and in doing so presenting Aldred with potential aplenty to continue this developmental and refreshingly formative arc for her character in months to come.

Where McCoy fares best is in his mirroring and evolution of the detached, uncharacteristically repulsive version of the Doctor glimpsed in Curse, the latter attribute central to the early stages of the narrative in which he and Ace are both literally and metaphorically separated not only by the gravity of Hex’s passing, but by the Time Lord’s inability to comprehend his friend’s grief in light of the frequency of meetings and partings such as these for a seasoned time traveller. An extended metaphor referenced by him and ex-TARDIS voyager Sally Morgan involves the concept of his companions being kites, the character himself being the one who controls them to varying avail, a notion which once again achieves its purpose of subverting our perspective on the titular wanderer’s morality magnificently.

Scribes before and after Fitton have and surely will continue to draw the line on this semi-psychological interrogation at this stage, yet to the immense benefit of Afterlife, Fitton steps once more unto the breach in his narrative’s final moments, teasing his audience with hints of the man who will become “a warrior” and seemingly commit double genocide in days to come as McCoy’s incarnation revels in his increasingly apt mythological title of “the Oncoming Storm” and the likelihood that, on occasion, his enemies could perceive him as “[their] worst nightmare”. Once the narrative’s final confrontation between its uncovered antagonist and its concerningly-omnipotent protagonist is done and dusted, it’s difficult to shake the sense that the Doctor has commenced a self-instigated psychological metamorphosis, whereby the character who represented nothing more than “a mild curiosity in a junkyard” to his first human onlookers has slowly but surely become a source of fear for the universe’s plethora of terrorising menaces, a thematic strand which of course only continues to build as we analyse and evaluate the implications of modern tales including The Pandorica Opens and A Good Man Goes To War today.

If you’ve noticed the omission of discussion of Afterlife’s alien adversary so far in this review, then feel free to treat yourself to a sizable bag of Jelly Babies and/or Jammie Dodgers at some point today: while her presence isn’t detrimental enough to derail the drama as a whole, Mandi Symonds’ Lily Finnegan (whose true identity this reviewer shan’t spoil, since the revelation itself is undoubtedly one of the narrative’s finest moments) is presented in a pantomime-esque manner at times, since the tiresome stereotypical representation of her Irish cultural roots (clearly intended by Fitton to act as a satirical element of comic relief) becomes more of a running gag than anything else in a rightly sombre storyline which could easily have done without it. It’s rare that Doctor Who’s inhabitance of the science-fiction genre proves to be disadvantageous for its scribes, but in this instance, Finnegan seems to be intended as little more than a means through which Fitton can assert his narrative’s (arguably unnecessary) conformation to the programme’s generic conventions.

Such is the mark of any great singular instalment of Who, however, that in spite of its minor shortcomings, the strength of its narrative, its performances and its construction prevail as the dominant elements for which we will remember and cherish it in the years following its debut. Afterlife is one such defining example of a chapter of this ilk, for quibbles regarding its slight structural blemishes and tonal missteps (the former manifesting as a result of the latter in Fitton’s somewhat awkward utilisation of Finnegan in the rushed cliff-hangers which tail-end Parts One and Two) become near-irrelevant in light of Fitton’s subversive, emotionally riveting script, Aldred and McCoy’s potent evolution of Ace and the Doctor’s personas respectively and a genuinely shocking final sequence which could set the Seventh Doctor audio range off on a completely unique trajectory with unprecedented consequences down the line (or to put it another way: “Change, my dear, and it seems not a moment too soon!”). This gripping audio drama is one of (if not the) best releases that Big Finish have produced in years, and consequently, it ranks up there with Doctor Who’s superior 21st Century works overall.

In stark contrast to recent Big Finish releases such as Dark Eyes 2, the premise of Fitton’s narrative is relatively straightforward: Thomas Hector Schofield (better known to Doctor Who fans as ‘Hex’) was killed by Fenric in 2012’s Gods and Monsters, a calamitous event which has (with good reason) turned Ace against the Doctor, leaving the latter to contemplate how to redeem himself after his being directly connected to the demise of one of his most loyal allies. Not since Earthshock and (albeit briefly) Time-Flight has a pre-21st Century Who yarn sought to have its eternal protagonist’s psyche and endless internalised guilt go quite so far under the microscope, and indeed, Fitton utilises the rarity of such a narrative opportunity as this to his significant advantage, providing a script which offers its lead stars their strongest material in years in terms of emotional and dramatic scope for future development. If there remain fans out in the big wide world who doubt Sylvester McCoy and Sophie Aldred’s talents, then this just might be the drama to convince them otherwise.

Inevitably, Ace is of the most paramount importance to the listener (and her ‘screen time’ reflects this suitably) as their entry point into proceedings, and to this degree, Aldred conveys beautifully the pathos of the character’s loss of a close friend, of someone who perhaps could have been something more than that had he not bitten the proverbial bullet before his time. Too often in the final episodes of the show’s 1980s run before its cancellation, this feisty and yet wholly sympathetic companion was cruelly robbed of a satisfying personal arc, with The Curse of Fenric coming the closest to matching Father’s Day and The Fires of Pompeii in its representation of its human protagonist’s utter disbelief at their extra-terrestrial hero’s detachment from emotion, yet still somehow falling short. In this respect, Afterlife excels without limits, casting Ace in an entirely new light and in doing so presenting Aldred with potential aplenty to continue this developmental and refreshingly formative arc for her character in months to come.

Where McCoy fares best is in his mirroring and evolution of the detached, uncharacteristically repulsive version of the Doctor glimpsed in Curse, the latter attribute central to the early stages of the narrative in which he and Ace are both literally and metaphorically separated not only by the gravity of Hex’s passing, but by the Time Lord’s inability to comprehend his friend’s grief in light of the frequency of meetings and partings such as these for a seasoned time traveller. An extended metaphor referenced by him and ex-TARDIS voyager Sally Morgan involves the concept of his companions being kites, the character himself being the one who controls them to varying avail, a notion which once again achieves its purpose of subverting our perspective on the titular wanderer’s morality magnificently.

Scribes before and after Fitton have and surely will continue to draw the line on this semi-psychological interrogation at this stage, yet to the immense benefit of Afterlife, Fitton steps once more unto the breach in his narrative’s final moments, teasing his audience with hints of the man who will become “a warrior” and seemingly commit double genocide in days to come as McCoy’s incarnation revels in his increasingly apt mythological title of “the Oncoming Storm” and the likelihood that, on occasion, his enemies could perceive him as “[their] worst nightmare”. Once the narrative’s final confrontation between its uncovered antagonist and its concerningly-omnipotent protagonist is done and dusted, it’s difficult to shake the sense that the Doctor has commenced a self-instigated psychological metamorphosis, whereby the character who represented nothing more than “a mild curiosity in a junkyard” to his first human onlookers has slowly but surely become a source of fear for the universe’s plethora of terrorising menaces, a thematic strand which of course only continues to build as we analyse and evaluate the implications of modern tales including The Pandorica Opens and A Good Man Goes To War today.

If you’ve noticed the omission of discussion of Afterlife’s alien adversary so far in this review, then feel free to treat yourself to a sizable bag of Jelly Babies and/or Jammie Dodgers at some point today: while her presence isn’t detrimental enough to derail the drama as a whole, Mandi Symonds’ Lily Finnegan (whose true identity this reviewer shan’t spoil, since the revelation itself is undoubtedly one of the narrative’s finest moments) is presented in a pantomime-esque manner at times, since the tiresome stereotypical representation of her Irish cultural roots (clearly intended by Fitton to act as a satirical element of comic relief) becomes more of a running gag than anything else in a rightly sombre storyline which could easily have done without it. It’s rare that Doctor Who’s inhabitance of the science-fiction genre proves to be disadvantageous for its scribes, but in this instance, Finnegan seems to be intended as little more than a means through which Fitton can assert his narrative’s (arguably unnecessary) conformation to the programme’s generic conventions.

Such is the mark of any great singular instalment of Who, however, that in spite of its minor shortcomings, the strength of its narrative, its performances and its construction prevail as the dominant elements for which we will remember and cherish it in the years following its debut. Afterlife is one such defining example of a chapter of this ilk, for quibbles regarding its slight structural blemishes and tonal missteps (the former manifesting as a result of the latter in Fitton’s somewhat awkward utilisation of Finnegan in the rushed cliff-hangers which tail-end Parts One and Two) become near-irrelevant in light of Fitton’s subversive, emotionally riveting script, Aldred and McCoy’s potent evolution of Ace and the Doctor’s personas respectively and a genuinely shocking final sequence which could set the Seventh Doctor audio range off on a completely unique trajectory with unprecedented consequences down the line (or to put it another way: “Change, my dear, and it seems not a moment too soon!”). This gripping audio drama is one of (if not the) best releases that Big Finish have produced in years, and consequently, it ranks up there with Doctor Who’s superior 21st Century works overall.