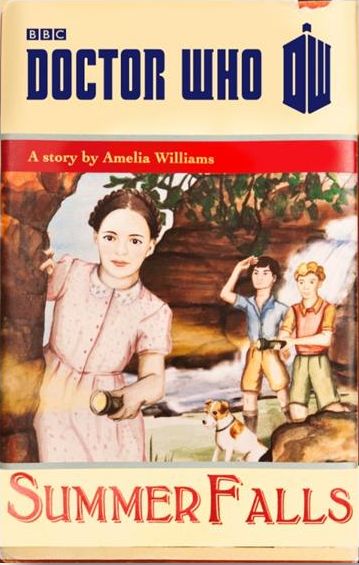

Summer Falls

Thursday, 11 April 2013 - Reviewed by Matt Hills

This review is based on the BBC Books' ebook and contains some spoilers

Summer Falls is a curious novella, more ‘Doctor fic’ than ‘Doctor lite’, since it’s supposedly written by Amelia Williams (formerly Pond) and involves a lightly fictionalized version of her Doctor. The ‘Curator’ has a mysterious “shed” in place of a Police Box, says very Doctorish things like “magic is cool” and “I love a little shoppe”, and is highly knowledgeable about all sorts of unusual entities and events. Oh, and the Curator also has a sort-of companion: one of the most brilliant, amusing companions that we’ll never get to see on-screen. No, it's not a shape-shifting talking penguin, but rather a grey talking cat, which enables real-world writer James Goss to explore all manner of great cat jokes. Essentially, what we learn is that cats do not fit at all well into the template of a Doctor Who companion, particularly given their tendency to get comfy and warm and have a doze mid-adventure, or their need to start cleaning rather than answering a question.

Returning to thoughts of Amy Pond strikes me as a faintly curious thing to do just as a new companion and a new mystery are launched in the TV series. Having Clara Oswald refer to an Amelia Williams’ story could be read as a passing of the baton; a way to honour and remember what’s come before as the franchise moves remorselessly on (and where everyone’s replaceable – not just companions, but even executive producers and showrunners). Perhaps this particular tie-in offers a kind of reassurance to fans of the Ponds. Amy hasn’t been erased from Who, after all, and the show is allowed to remember her in its passing details. Either that, or there’s method to the reminiscence, and Steven Moffat doesn’t want audiences to forget Amelia for a specific, yet-to-be-revealed reason. Given that ‘The Angels Take Manhattan’ was so insistently book-ended, circling back to ‘The Eleventh Hour', for this story/character thread to be picked up again so soon feels strange at the very least.

For my money, James Goss has consistently been one of the best recent writers of original, off-screen Doctor Who and Torchwood, and there's a tendency towards playful pastiche evident across his work. He’s a strong choice for this sort of material, given that Summer Falls was supposedly first published in 1954, and so is tailored to resemble a quaint, mildly jolly-hockey-sticks children’s fantasy adventure. Not only does it not feature the Doctor (by name), it’s also strongly fantastical rather than science-fictional, a genre shift which Who itself occasionally indulges in, but which seems to have dismayed some audiences of late with regards to ‘The Rings of Akhaten’. Although Summer Falls has the Doctor-type character muttering about “psycho-temporal” factors, it doesn’t really make very much effort to pin matters down into a science fiction template, instead preferring the broader poetic license of talking cats, frozen seas, and strange, powerful objects which have to be collected.

Goss repeatedly toys with readerly expectations. Summer Falls features the Lord of Winter, which in a novella released shortly before ‘Cold War’, and not long after ‘The Snowmen’, one might guess would implicate either the Ice Warriors or the chilly Great Intelligence. What we get remains tantalizingly vague, and I’m not at all convinced that this tale ties into ongoing series 7 events in any unexpected way. Of course, the big gimmick is that Summer Falls appeared on screen in ‘The Bells of Saint John’, meaning that we’ve already seen its heroine Kate depicted as a Spoonhead, as well as knowing that Chapter 11 is a tear-jerker (something it strives to live up to). This creates a complex layering of fiction-upon-fiction: the real book that you can buy and enjoy is itself part of the Doctor Who universe, as well as featuring a fictionalized version of the Doctor. When will Clara ask the Time Lord if he’s really the Curator? Will this fiction-within-a-fiction be played with in the TV show itself, I wonder, even perhaps in its anniversary special? I’d hazard not, however: the reference-spotting of Summer Falls suits fandom all too well – it’s a sort of roman à clef revolving around a key which has to be found, while readers can use the master key of Doctor Who to interpret what’s going on. But I’m not convinced that such "meta" would necessarily translate well to the broader mass audience of Christmas and Anniverary Specials, so perhaps ‘Doctor fic’ will remain a little-known tie-in subgenre for now.

Having said that, I’d like to see a series of Amelia Williams’ tales, perhaps written at different times across her life, each giving a different refraction and revision of her adventures. Re-fictionalized alt-Daleks or Screaming Cherubs could get an outing. Pursued as a series of reimagined slants on the Moffat era, this sort of playful Who manqué could start to build up into far more than the sum of its parts. But as things stand, and as a one-shot, Summer Falls is a clever, cool experiment in meta that doesn’t always feel like it really matters to ongoing arcs and questions.

Summer Falls is a curious novella, more ‘Doctor fic’ than ‘Doctor lite’, since it’s supposedly written by Amelia Williams (formerly Pond) and involves a lightly fictionalized version of her Doctor. The ‘Curator’ has a mysterious “shed” in place of a Police Box, says very Doctorish things like “magic is cool” and “I love a little shoppe”, and is highly knowledgeable about all sorts of unusual entities and events. Oh, and the Curator also has a sort-of companion: one of the most brilliant, amusing companions that we’ll never get to see on-screen. No, it's not a shape-shifting talking penguin, but rather a grey talking cat, which enables real-world writer James Goss to explore all manner of great cat jokes. Essentially, what we learn is that cats do not fit at all well into the template of a Doctor Who companion, particularly given their tendency to get comfy and warm and have a doze mid-adventure, or their need to start cleaning rather than answering a question.

Returning to thoughts of Amy Pond strikes me as a faintly curious thing to do just as a new companion and a new mystery are launched in the TV series. Having Clara Oswald refer to an Amelia Williams’ story could be read as a passing of the baton; a way to honour and remember what’s come before as the franchise moves remorselessly on (and where everyone’s replaceable – not just companions, but even executive producers and showrunners). Perhaps this particular tie-in offers a kind of reassurance to fans of the Ponds. Amy hasn’t been erased from Who, after all, and the show is allowed to remember her in its passing details. Either that, or there’s method to the reminiscence, and Steven Moffat doesn’t want audiences to forget Amelia for a specific, yet-to-be-revealed reason. Given that ‘The Angels Take Manhattan’ was so insistently book-ended, circling back to ‘The Eleventh Hour', for this story/character thread to be picked up again so soon feels strange at the very least.

For my money, James Goss has consistently been one of the best recent writers of original, off-screen Doctor Who and Torchwood, and there's a tendency towards playful pastiche evident across his work. He’s a strong choice for this sort of material, given that Summer Falls was supposedly first published in 1954, and so is tailored to resemble a quaint, mildly jolly-hockey-sticks children’s fantasy adventure. Not only does it not feature the Doctor (by name), it’s also strongly fantastical rather than science-fictional, a genre shift which Who itself occasionally indulges in, but which seems to have dismayed some audiences of late with regards to ‘The Rings of Akhaten’. Although Summer Falls has the Doctor-type character muttering about “psycho-temporal” factors, it doesn’t really make very much effort to pin matters down into a science fiction template, instead preferring the broader poetic license of talking cats, frozen seas, and strange, powerful objects which have to be collected.

Goss repeatedly toys with readerly expectations. Summer Falls features the Lord of Winter, which in a novella released shortly before ‘Cold War’, and not long after ‘The Snowmen’, one might guess would implicate either the Ice Warriors or the chilly Great Intelligence. What we get remains tantalizingly vague, and I’m not at all convinced that this tale ties into ongoing series 7 events in any unexpected way. Of course, the big gimmick is that Summer Falls appeared on screen in ‘The Bells of Saint John’, meaning that we’ve already seen its heroine Kate depicted as a Spoonhead, as well as knowing that Chapter 11 is a tear-jerker (something it strives to live up to). This creates a complex layering of fiction-upon-fiction: the real book that you can buy and enjoy is itself part of the Doctor Who universe, as well as featuring a fictionalized version of the Doctor. When will Clara ask the Time Lord if he’s really the Curator? Will this fiction-within-a-fiction be played with in the TV show itself, I wonder, even perhaps in its anniversary special? I’d hazard not, however: the reference-spotting of Summer Falls suits fandom all too well – it’s a sort of roman à clef revolving around a key which has to be found, while readers can use the master key of Doctor Who to interpret what’s going on. But I’m not convinced that such "meta" would necessarily translate well to the broader mass audience of Christmas and Anniverary Specials, so perhaps ‘Doctor fic’ will remain a little-known tie-in subgenre for now.

Having said that, I’d like to see a series of Amelia Williams’ tales, perhaps written at different times across her life, each giving a different refraction and revision of her adventures. Re-fictionalized alt-Daleks or Screaming Cherubs could get an outing. Pursued as a series of reimagined slants on the Moffat era, this sort of playful Who manqué could start to build up into far more than the sum of its parts. But as things stand, and as a one-shot, Summer Falls is a clever, cool experiment in meta that doesn’t always feel like it really matters to ongoing arcs and questions.