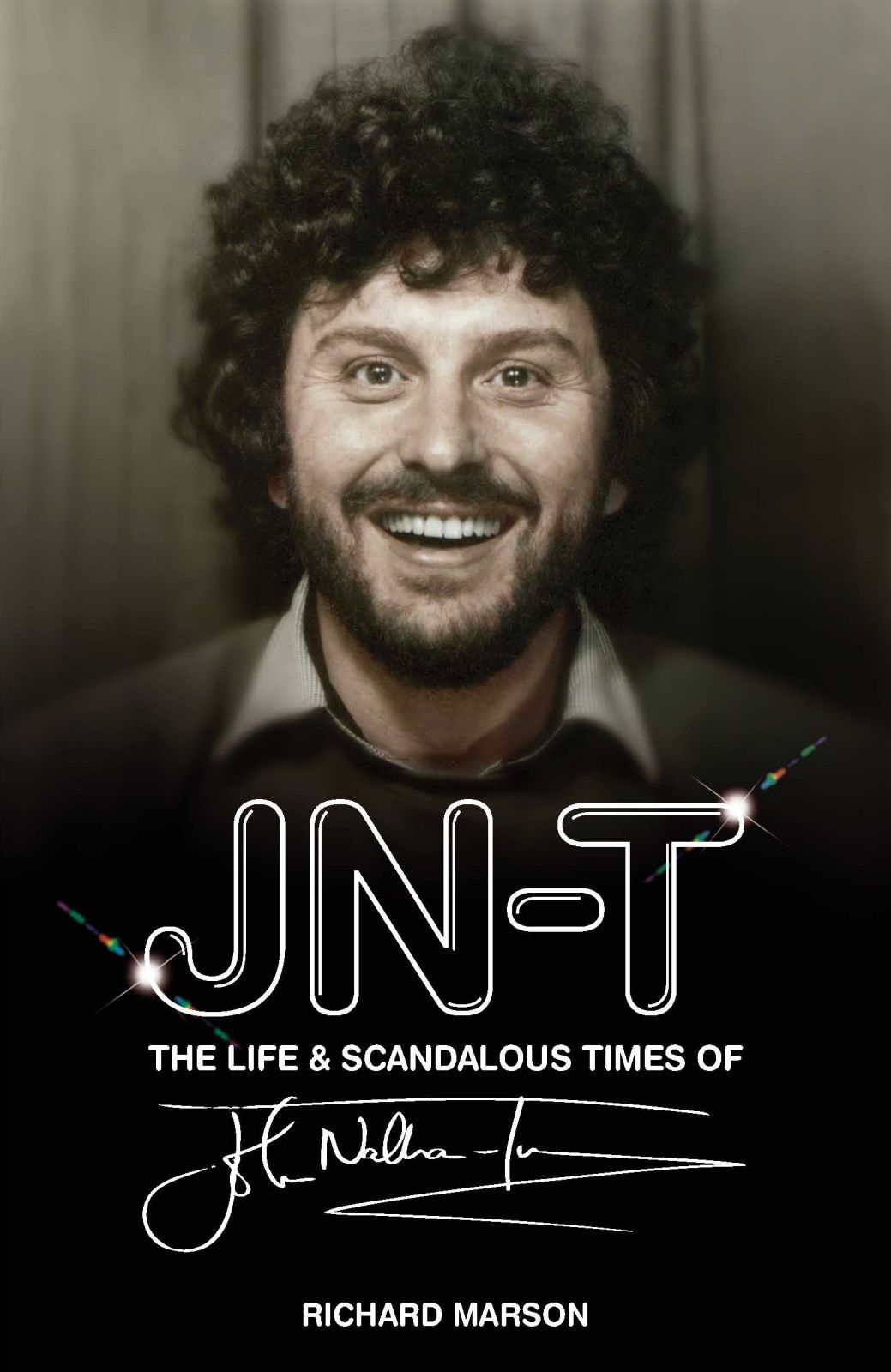

The Life and Scandalous Times of John Nathan-Turner

Tuesday, 9 April 2013 - Reviewed by

The Life and Scandalous Times of John Nathan-Turner

Written by Richard Marson

Published by Miwk Publishing

Released April 2013

I can distinctly remember noticing the features by John Nathan-Turner, an instantly recognisable name to any Doctor Who fan. He was a familiar figure from documentaries such as More Than Thirty Years in the TARDIS, and I’d read his memoirs serialised in DWM not long before. With a name like that it couldn’t be anybody else, and he even had his own byline photo to confirm it.

His features in the Argus were interviews with minor local celebrities, usually actors. I don’t remember how many of them he did – Richard Franklin is the only one that I specifically recall – but I do very clearly remember thinking, and even saying to my dad, “That’s a bit sad, he used to produce Doctor Who – how come he’s ended up writing cheap showbiz features for a local paper?”

As JNT: The Life and Scandalous Times of John Nathan-Turner reveals, the whole of Nathan-Turner’s post-Doctor Who career, which has perhaps been something of a mystery to fandom, could be described as being “a bit sad”. His name had become mud at the BBC, and despite a series of increasingly desperate and bizarre pitches, he was never able to persuade any broadcaster to work with him again, or to take up any of his programme ideas.

Richard Marson has done excellent work with this book, delving into the life and career of a man who seems utterly familiar on the one hand to Doctor Who fans, but who really it seems we only ever knew a certain side of, in a certain way. It’s the tragedy of many who are associated with Doctor Who that they are remembered only by us, and only for their Doctor Who careers – but Nathan-Turner’s association with the show became a burden even while it was ongoing.

Marson, a former producer and then editor of Blue Peter, himself points out the parallels between himself and his subject – both producers of long-standing, iconic BBC television series, who ended up having somewhat bitter partings from the programmes they had loved. But just because Marson has some empathy for Nathan-Turner, don’t make the mistake of thinking this book ever strays into the territory of being a hagiography – indeed, as you may have noticed from some of the press attention it has garnered, it’s anything but.

The fact that Marson is unafraid to tackle head-on some of the less pleasant aspects of Nathan-Turner’s character – and, to a greater extent, those of his partner Gary Downie – caused argument and debate in fandom in the weeks before the book was even released. There are some who are appalled by the revelations in the book. Some who are appalled that accusations have been made against men who are no longer alive and unable to defend themselves. Some simply embarrassed that Doctor Who has become associated with such squalor in its anniversary year, and particularly in the wake of the wider scandals that have engulfed the BBC in recent months.

It’s true that this book would almost certainly not have been written, at least not in this way, while Nathan-Turner and Downie were still alive. But that’s probably true of almost any honest biography, and time and distance can help to lend a vital objectivity. While it’s also true that the book contains details some Doctor Who fans may find unpleasant reading, in the same way that the book is not a hagiography, it’s never a hatchet job either. Marson is scrupulous in reproducing as many points of view and versions of events as possible, putting quotes from various interviewees one after the other to offer all the different sides of an argument, or versions of events.

The reader is left to make up his or her own mind about Nathan-Turner. Myself, I was chiefly left with the impression of a man I personally wouldn’t have ever wanted to know, but at the same time also a man rather sadly crushed by circumstances, and by a changing world at the BBC.

‘The BBC’ – dangerous as it always is to regard it as a single-minded monolith – almost comes across as a personality and a character in its own right in the narrative, and how interesting you find the book may depend on how much of an interest you have in the internal workings of the drama department, in the days of multi-camera videotape drama being made at Television Centre. I personally find such things fascinating, and it’s a real treat to get an insight into the labyrinthine workings of the Corporation and its drama department in the 1970s and 80s. It’s fair to say, however, that others may find such things less involving, and if you’re not really enthused by the structures and workings of the BBC drama department then this is possibly not the book for you.

Doctor Who fans generally, however, do tend to be interested in the behind-the-scenes workings of the show they love, perhaps more so than fans of any other television series. It’s why Doctor Who is quite possibly the most well-documented television programme ever made and why, as Russell T Davies once pointed out, in generations to come it will be the case study for how British television drama was made.

You sometimes have to remind yourself when reading this book that the fans do actually love the show, however. There are times when fandom comes across as being utterly repulsive and full of unpleasant people. I realise this isn’t entirely representative of how fandom was in the 1980s any more than the worst bitchers and moaners of Gallifrey Base or Roobarb's Forum represent it now, but I have to say I am rather glad I wasn’t old enough to be anywhere near fandom at the time. We perhaps don’t always appreciate how lucky we are in the 21st century, when fandom is so much larger, and online. If there’s a particular website or group of people you can’t get on with, you can easily find another place to share your love of the show, with people and things that make you laugh. No longer do you simply have to put up with whoever happens to attend your local group meeting.

Doctor Who and fandom recovered from the – at times – dark days portrayed in this book. But the shame of it is that Nathan-Turner never got the chance to. But on the other hand, I think he would have been pleased that he’ll be remembered, and that’s where the curse of Doctor Who is at least paying him something back. Jonathan Powell – refreshingly honest as an interviewee here – may well have been a far superior drama producer to Nathan-Turner, with a track record the latter couldn’t hope to match. He’s produced several BAFTA-winning productions of high quality. But he’ll never have a biography written about him. Nobody will ever research his life in detail, track down and speak to his teachers and schoolfriends. Trace the progress of his career in television, from the studio floor to the producer’s chair. When he dies, it will be little-noted outside of his friends and family.

Doctor Who can destroy careers. But Doctor Who fans remember. And because Doctor Who fans tend to be creative and industrious, we end up with superb books like this one. It’s not always an easy read, but I would recommend The Life and Scandalous Times of John Nathan-Turner to anyone with even a casual interest in television history in general, and Doctor Who’s history in particular.