Doctor Who and The Talons of Weng-Chiang (AudioGo)

Monday, 28 January 2013 - Reviewed by

The Talons of Weng-Chiang

Starring Tom Baker

Written by Terrance Dicks

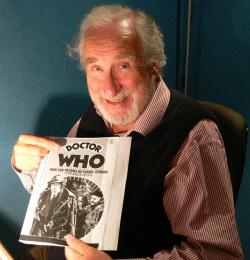

Narrated by Christopher Benjamin

Released by BBC AudioGo, January 2013

All these programmes were fed by the fact that in the 1970s the end of the Victorian period was just within or just outside living memory. Pennies and ha’pennies of Queen Victoria weren’t difficult to find in my (post-Victorian) grandparents’ house. Britain had spent most of the twentieth century trying to live up to an imperial myth largely manufactured in the late nineteenth century, of an empire where the sun never set and where British arms and British ships, military and merchant, dominated the globe. Just over thirty years before, Britain had fought, it thought, to defend that empire; by 1977 that empire was gone and with it economic self-assurance and a secure sense of national identity. However, historical dramas set in the Victorian period didn’t just compensate for national bewilderment; they were a reminder of a society from which mid-twentieth century Britain had escaped, one of poverty and disease and rigid conventions governing relations among classes, genders and ethnic groups. At the same time, the culture of British industry still owed much in the 1970s to the Victorian age; it was one where trade unions pointed both to the craft skills of their nineteenth-century predecessors and to the battles won by them for fair wages and working hours, and where managing directors still based their businesses on heavy machinery which had not changed greatly in eighty years. While for Doctor Who’s child audience, its eyes fixed on the twenty-first century, the 1890s of The Talons of Weng-Chiang might seem like ancient history, for many of the adults watching the 1890s might not have felt a long time distant.

This sense of time displacement is relevant to consideration of the book and the audio. One of the first things Christopher Benjamin’s vinicultured voice brings out is how careful Terrance Dicks was to explain the nuances of the story’s setting to his target audience of children reading Doctor Who and the Talons of Weng-Chiang by themselves. With the visual element removed, the written and spoken word both rely on Dicks’s depiction of the social hierarchy of the music hall audience for initial contextualisation. This opens the first chapter and introduces music hall as something which appeals to all classes in the 1890s, but which does not unite them: ‘toffs’, ‘bank clerks and shop assistants’, ‘Labourers, dock workers, soldiers and sailors, even some of the half-starved unemployed’ are all present but all in places assigned by their spending power. The effect is more raw than that conveyed by the well-groomed audience seen on television at the Royal Theatre, Northampton. It also conveys something of the gap between the welfare state of a 1970s Britain which thought itself egalitarian and an 1890s London which had no social safety net and where class distinctions were dominant in a way easily comprehensible to the child readership.

Terrance Dicks’s attention to replacing lost visual and aural cues with new written detail friendly to an intelligent young audience also applied to characters. Listeners to Doctor Who and the Talons of Weng-Chiang will hear Christopher Benjamin relate Dicks’s outline of Litefoot’s background as the rebel member of a family with aristocratic connections, and his resigned tones as the elderly waterman spitting his way through life, baffled at the expedition undertaken by the Doctor and Litefoot complete with giant fowling pistol. Dicks’s invention of Teresa’s occupation as ‘a waitress in a gambling club, in Mayfair on the other side of London’ compensates for the loss of Teresa’s costume and make-up, which some viewers have understood as representing a profession unsuitable for children’s literature. Christopher Benjamin’s falsetto Teresa is a brave attempt at youthful feminine joie-de-vivre, but his real strength is the matter-of-fact relation of events which he steadily leavens with urgency and horror as Chang presents his victims to a suitably maniacal Greel.

As 1977 has receded into the past, so John Bennett’s appearance as Li H’sen Chang, a white European actor under pseudo-oriental prosthetics, has caused more and more pained expressions among admirers of the story. Terrance Dicks, in an allusion to the cultural baggage Bennett’s casting and make-up carried with it, contrasted Chang with ‘most Oriental magicians who were usually English enough once the make-up was off’. Chang’s name recalls that of Chung Ling Soo, really the American-born William Ellsworth Robinson, killed when a trick went awry at the Wood Green Empire in north London in 1918. It’s possible that Robert Holmes’s choice of name for his Chinese magician was based on the expectation that an actor of western appearance would play Chang under make-up. Bennett’s casting in this vein drew attention to the artifice of Doctor Who and its reliance on a showbusiness tradition of deception, as well as an exoticism which portrayed the Chinese as unquestionably ‘the Other’. Dicks’s reference in the text acted as a historical note and placemarker for a visual gag at the expense of both conventions which could not be reproduced on the page. However, the fiction of Sax Rohmer, whose Fu Manchu is based on the assumption that world affairs were a competition between easily-defined ‘races’, would still have been current in the childhood of many parents and grandparents watching. The film series starring Christopher Lee was a very recent memory.

Chang’s character is based as much on an understanding of the audience at home as white British as it is upon Chang’s manipulation of the prejudices of the white community. Chang is used, of course, to emphasise the Doctor’s own Otherness – ‘Are you Chinese?’ reminds the hypothetical white British viewer and listener that the Doctor does not share their prejudices. A twenty-first century restaging might seek to reinterpret Chang for a more broadly-conceived audience, but this is not an option here. Christopher Benjamin reads the speeches of Li H’sen Chang in a stage Chinese which suits the status quo, but Chang is now doubly a recreation of past attitudes, steeped in an irony which has lost some power since the 1970s. Nevertheless Benjamin recognises that for all his crimes, Chang is a person to be treated with some sympathy, and his reading of his final scene has the distance of someone dulling with opium the torment of moral self-realisation as well as his physical agony.

Admirers of Leela might feel disappointed by this audiobook. In Benjamin’s reading, Leela is more of a simpleton than she appeared on television, lacking the self-assurance Louise Jameson brought to the role. Dialogue of which Louise Jameson made the most – such as ‘You ask me so that you can tell me’ – is flattened and made more submissive than Jameson performed it on television. Benjamin, though, adequately represents Terrance Dicks’s interpretation of Leela as a childlike innocent in thrall to the Doctor’s genius, whose bravado often exceeds her bravery, difficult though that position is to reconcile with many of Leela’s actions in this story.

Christopher Benjamin’s Doctor is difficult to pin down, not least because he doesn’t seem to have a fixed interpretation. For long periods his intonation is reminiscent of Tom Baker’s deep ringing tones, without capturing them, and at other times there is a mercurial self-satisfied air reminiscent of the Doctor with which Benjamin has worked most recently, Colin Baker. (Admirers of the Jago and Litefoot double act might find that Benjamin’s Litefoot is reminiscent of Trevor Baxter.) However, there is occasionally a glimpse of another Doctor, a gruff and amiable Time Lord who casts a sometimes sternly avuncular gaze over proceedings. The portrayal of the Doctor in a performed reading of a novelisation encourages expectations in a reader and while Benjamin is always authoritative there are too many different voices there to feel one is listening to a consistent portrayal; or perhaps the legacy of Tom Baker looms too large.

Christopher Benjamin’s Doctor is difficult to pin down, not least because he doesn’t seem to have a fixed interpretation. For long periods his intonation is reminiscent of Tom Baker’s deep ringing tones, without capturing them, and at other times there is a mercurial self-satisfied air reminiscent of the Doctor with which Benjamin has worked most recently, Colin Baker. (Admirers of the Jago and Litefoot double act might find that Benjamin’s Litefoot is reminiscent of Trevor Baxter.) However, there is occasionally a glimpse of another Doctor, a gruff and amiable Time Lord who casts a sometimes sternly avuncular gaze over proceedings. The portrayal of the Doctor in a performed reading of a novelisation encourages expectations in a reader and while Benjamin is always authoritative there are too many different voices there to feel one is listening to a consistent portrayal; or perhaps the legacy of Tom Baker looms too large.Benjamin’s voice is good at conveying the self-consciously heightened sense of danger in Dicks’s economical prose. Much of The Talons of Weng-Chiang depends upon the unknown lying beneath the familiar; so there is trepidation as manhole covers are removed and a deliberate, heavy wariness as characters wade through the filthy, rat-infested sewers. Benjamin and Dicks tell of a London dark and treacherous in its diversity, which it takes the universalist outsider, the Doctor, to navigate appropriately. There are some cautious notes - there seems to be care, for example, not to make ethnic epithets as emotively-charged as they might have been performed on screen in 1977.

There are some memorable moments of sound engineering in this audiobook. The echo placed over Christopher Benjamin’s voice in the pathology lab scenes almost dispel associations with the cramped tiled room and its anachronistic electric sockets covered by even more anachronistic adhesive plastic in the television production. The giant rats are relieved of the burdensome necessity of appearing in the fabric-and-stuffing, and can rely on piercing shrieks alone to instil terror into the heart of the listener. There are not quite as many porcine grunts from Mr Sin as I expected, but care has to be taken not to undermine the reader’s performance. Instead, one can sometimes imagine Christopher Benjamin moving from pathology lab to the night streets of Limehouse, climbing down into Greel’s hidden chamber as a silent companion opens the hatch for him, or hauling himself up in the dumb waiter in an attempt to escape from Greel’s clutches. Despite the reservations above, it’s an admirable reading, with Benjamin moderating his Henry Gordon Jago so as not to overwhelm his narrator’s voice, but not obliterating it; the way he uses his delivery to highlight the differences of class and education between Jago and Litefoot when they meet is a particularly skilled performance.

A release of a science fiction or fantasy story set in Victorian London in 2013 raises a question of genre unknown in 1977. Can Doctor Who and the Talons of Weng-Chiang be described as steampunk? If steampunk depends on a situation where ‘anachronism is not anomalous but becomes the norm’, as Rachel A. Bowser and Brian Croxall wrote in their introduction to volume 3, part 1 of the journal Neo-Victorian Studies (available free at www.neovictorianstudies.com), then novelisation and audiobook perhaps score less highly than the broadcast version. Terrance Dicks describes Greel’s organic distillation equipment simply as ‘ultra-modern’, which isn’t adequate to the baroque eclecticism of the machinery seen on television. Mr Sin and the Eye of the Dragon fuse the futuristic with cultural signifiers of the ‘old’ in book form as well as on television, though the audiobook’s blaster sound effects probably reinforce the high-tech connotations at the expense of the image of the gold dragon from which the blaster is fired. Even as a digital download in 2013, Doctor Who and the Talons of Weng-Chiang remains the product of a mechanical age when the dissonance between inexplicable futuristic technology and Victorian machinery was more powerful than the imagining of impossibly world-transforming engines; its lacquered Time Cabinet is a gateway for a generic reading which from the book’s own point of view in 1977 has yet to emerge from it.

Whatever the problems it inherits from its source, Doctor Who and the Talons of Weng-Chiang remains a hugely entertaining story and there is much to discover in Christopher Benjamin’s reading. Linger over descriptive passages and muse on how Magnus Greel’s ramblings about time agents and the Doctor’s counter-revelations about the battle of Reykjavik came to influence the programme’s mythology. Hear how both the Doctor and Leela confound the Holmes-Dicks pastiche of late Victorian manners which for all their assumed superiority are no match for the foe from the future. That the story measures its imagined past against a present day which is now very much our history, however recent, only adds another level of curiosity to one of Doctor Who’s pivotal tales.