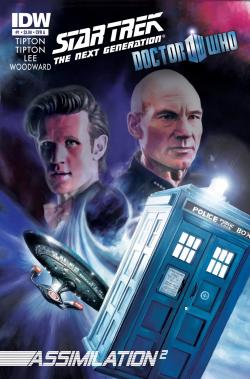

IMW: Star Trek: TNG/Doctor Who: Assimilation2

Sunday, 24 February 2013 - Reviewed by

Star Trek: TNG/Doctor Who: Assimilation2

IMW

Written by Scott and David Tipton, Tony Lee

Released as a collection in 2012 (Vol1/Vol2)

Even Star Trek has had its crossovers. The Enterprise crews of Captains James T Kirk and Jean-Luc Picard teamed up with the X-Men in the Nineties and Kirk’s crew recently met the Legion of Super Heroes. Doctor Who, however, has avoided entangling itself with other TV/film tie-ins.

In 2012, that changed when IDW, publisher of Doctor Who and Star Trek comics, printed Assimilation2, an official Star Trek: The Next Generation/Doctor Who crossover (endorsed by Paramount and the BBC). This eight-issue mini-series (recently collected in two volumes by IDW) paired the Eleventh Doctor, Amy and Rory with the crew of the Enterprise-D to protect the United Federation of Planets from a Borg/Cybermen alliance.

When IDW announced the project, there was promise of an epic tale. Sadly, the mini-series fails to live up to that ambition. Writers Scott Tipton, David Tipton and Tony Lee have all delivered some fantastic stories for IDW’s Doctor Who comic (Lee’s The Forgotten is outstanding) and for this crossover, they are highly respectful of both properties. However, as a story, it seems the scope of the brief may have been too grand and ambitious, even for them.

Assimilation2 is way too long. IDW thinks an epic should be eight issues. Instead of an action-packed, tightly-paced story over four to six issues, we have an adventure that plods along, despite the scale of the extra-dimensional threat. Indeed, the first two issues are studies in how different modern Doctor Who is in tone and tempo to Star Trek: The Next Generation.

The first issue sees the Doctor, Rory and Amy complete an adventure in ancient Egypt, exposing an alien criminal masquerading as the Pharaoh’s vizier. The second issue focuses on the Enterprise-D’s visit to ocean world Naia VII, where Starfleet is involved in an intensive mining operation to extract materials for the return bout with the Borg. The first chapter is evocative of modern Doctor Who, with the TARDIS team thrown into the thick of trouble. The second chapter is a dull, staple Next Generation episode, with the crew doing little exciting or consequential. Sadly, when the story proper begins halfway through Issue 2, its tenor and pace continues to mirror the staidness of ST:TNG and not Who’s vigour and wit.

When you expect Issue 3 to ramp up the story, it is sidetracked by a pointless flashback in which the Fourth Doctor aids Captain Kirk and his away team against a Cyberman raiding party (of the Revenge of the Cybermen caste). Once that mini-adventure is over, it takes another two issues for the Eleventh Doctor to convince Picard to trust him and overcome his suspicion/hatred of the Borg – and that’s not until Issue 5! It’s then another three issues before the TARDIS and Enterprise-D crews take the fight to the enemy. When events come to a head in Issue 8, the climax is disappointing.

The story follows the typical formula of crossover comics. There is uneasiness and distrust amongst the protagonists while the antagonists predictably turn on each other. For example, just as Batman and Judge Dredd have to overcome their differences to outwit the Joker and Judge Death, so it takes a good few issues for the Doctor and Picard to agree on a partnership for the greater good. Meanwhile, the Cybermen prove more than a match for the Borg, which tests credibility. Largely because of Doctor Who’s constrained TV budget in the past, the Cybermen have always been the poorer cousins to the Borg, lacking their resources and firepower. Yet they usurp their Trek universe counterparts with ease and in the bargain threaten two universes. Given the short shrift they have had in Doctor Who (going from chilling metal giants to figures of parody in a few stories), making the Cybermen “the big bad” is a good idea. Unfortunately, the Cybermen’s aggressive behaviour is more characteristic of the Daleks (I suspect IDW’s preference for a Dalek/Borg alliance would have been vetoed by Terry Nation’s estate). Certainly the Cybermen’s portrayal (characterised by the Borg-enhanced Cyber Controller in Issue 8) contradicts the single-mindedness and logic of the steel giants.

The characterisation of the protagonists is faithful and consistent with their TV portrayals. The Tiptons capture Matt Smith’s Doctor’s eccentric and madcap persona and contrast it well with Picard and Riker’s earnestness. What doesn’t work is Picard’s attitude to the Borg. While Picard’s behaviour is consistent with episodes of TNG post-The Best of Both Worlds, it is undermined by the fact that this sequence of events occurs during the Enterprise-D’s seven-year mission and before the events of Star Trek: First Contact. In fact, the way Picard overcomes his reservations about his perennial foe contradicts Patrick Stewart’s brilliant performance in First Contact (when we see just how bitter Picard is about the Borg).

As can be expected with an ensemble cast, the story is unkind to most of the TNG characters. The Doctor, Picard, Data and Riker dominate the “screen time” and dialogue, Worf gets a few good action scenes but LaForge, Crusher and Troi are grossly underused. Amy and Rory are also relegated to observer status but still feature in the story more than the unlucky trio.

Although her presence in the story is also brief, the Doctor’s meeting with the Enterprise-D’s enigmatic bartender Guinan is the highlight of the comic. Guinan is what the Doctor would call a “time sensitive” who can perceive differences in the flow of time (witnessed in TNG episode Yesterday’s Enterprise). She is the perfect foil, throwing the Time Lord with her ability to read him. “I must admit, you have me at a ... loss ... that doesn’t happen ... often,” he muses. This example of character interaction works well, fulfilling a function common in crossovers – highlighting specific characters’ differences and eerie similarities.

Unfortunately, other character relationships don’t fare so well. There are brief, memorable exchanges. The TARDIS crew’s arrival on the Enterprise is amusing (Data confuses the TARDIS crew for malfunctioning hologram simulations) as is the Doctor’s retort to Riker when the commander scoffs that he could be 100 years old: “Don’t be ridiculous, Commander. I’m nowhere near 100.” When Worf declares his usual mantra that “Today is a good day to die,” Rory’s comeback is “I never much care for it myself ...” But for the most part, this kind of banter is limited and the story is mostly humourless.

While the story disappoints, JK Woodward and Gordon Purcell’s interior artwork is stunning. Purcell pencils and inks the story and Woodward paints, contributing to a look that echoes peer Alex Ross’s work. In close up, most of the characters resemble their TV counterparts and the look is so organic (compared to other comics) that when the Fourth Doctor/original Trek crew flashback occurs in Issue 3 and the art reverts to a traditional comic book style, you are sadly reminded that you are reading a comic!

Each of the eight issues had regular and retailer incentive covers, with the standouts belonging to Woodward for his Borg/Cyberman combo to Issue 2 and Issue 3’s fantastic cover art of Revenge-style Cybermen menacing Captain Kirk. Special mention also goes to some of Joe Corroney’s alternate covers, particularly the Issue 1 RI cover putting the Doctor, Rory and Amy in charge of the Enterprise, and the Issue 3 homage by Elena Casagrande and Ilaria Traversi to the movie poster for Star Trek: First Contact.

Unfortunately, while the cover and interior artwork is impressive, it emphasises that Assimilation2 is all style, no substance. I certainly don’t envy the task the writers and artists had but despite their best efforts, we have a story that, like many blockbuster films, over-promises and under-delivers. Nevertheless, the story is plausible enough that you can believe the Doctor and Guinan can chat like old friends, Amy and Rory can have a quiet discussion with Troi, and Data would be unfazed by the TARDIS’s interior dimensions. This convinces me, despite the faults of Assimilation2, that there is scope for future Doctor Who/Star Trek crossovers. Given IDW has the comic book rights to JJ Abrams’ incarnation of Star Trek, pairing Matt Smith’s Doctor with Chris Pine’s Kirk and Zachary Quinto’s Spock is recommended – or perhaps IDW should go out on a limb and pair the Doctor with Captain Kathryn Janeway and the USS Voyager in the Delta Quadrant ...

At any rate, the next crossover should be promoted as Doctor Who/Star Trek! It irks that Star Trek had top billing, especially when Doctor Who is the live TV program and TNG expired over a decade ago with Star Trek: Nemesis! But that’s just a minor gripe ...

Star Trek: The Next Generation/Doctor Who: Assimilation2 is available in two trade paperback volumes by IDW Publishing: Volume 1 (ISBN 978-1613774038) and Volume 2 (ISBN 978-1613775516).